- Life

- Work

- Timeline

- Joyce’s Dublin

- Resources

Timeline

James Joyce lived from 1882 to 1941. Find about more about the various stages of his life.

There are some references to Joyce’s earliest writings. His younger brother Stanislaus recalled essays written while the family lived in Blackrock, and James’s early collaborative effort with a local boy called Raynold. Perhaps a milestone in Joyce’s early writing career, Stanislaus also recalls a poem written upon the death of Charles Stewart Parnell when James was nine years old. The poem, entitled “Et Tu, Healy”, was an attack on Tim Healy, nationalist MP and member of Parnell’s Irish Party, who rejected Parnell over the divorce scandal that rocked Parnell’s career. James’s poem, influenced by the staunch Parnellism of his father John Joyce, ended with Parnell positioned as an eagle, overlooking a squabble of Irish politicians from

his quaint-perched aerie on the crags of Tim

Where the rude din of . . . century

Can trouble him no more

John Joyce had the poem printed and distributed, allegedly sending a copy to the Pope.

During his time at school, Joyce began writing more consciously. He won some essay-writing and English composition competitions. Meanwhile, he composed two collections of poetry, entitled Moods and Shine and Dark, though neither survive. A more important development in his writing career was when he began writing short stories, entitled “Silhouettes”. These short sketches were an early precursor to Joyce’s “epiphanies”, which would later form the backbone of Dubliners.

Joyce’s years at University College Dublin were marked by increased creative output. In January 1900, he published a review of Henrik Ibsen’s play When We Dead Awaken for The Fortnightly Review. He also published, though with some difficulty, an essay entitled “The Day of the Rabblement”, critiquing the contemporaneous politics and culture of the Irish Literary Revival. The essay was censored and pulled from publication in the St. Stephens magazine, and was consequently published in a pamphlet with an essay by fellow classmate Francis Sheehy Skeffington. He also published poems in issues of Dana and The Speaker.

Joyce began work on short stories more fervently in 1904, often at the behest of George Russell. In The Irish Homestead, he published “The Sisters” in July, “Eveline” in September, and “After the Race” in December 1904. Although he was paid £1 per story, Joyce published the stories under the name Stephen Daedalus, to avoid association with The Irish Homestead and its disparaging nickname “The Pig’s Paper”.

During his regular publications with The Irish Homestead, Joyce wrote to his friend Con Curran in July, telling him “I am writing a series of epicleti—ten—for a paper. I have written one. I call the series Dubliners to betray the soul of that hemiplegia or paralysis which many consider a city”.

While working on the stories for Dubliners, Joyce was also working on chapters for what would become A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man from as early as February 1905. Many of his more celebrated works were written while living abroad, notably in European cities such as Trieste, Pola, and Paris.

Joyce finished much of the preliminary writing of Dubliners by 1907, and also published a book of poetry entitled Chamber Music. The next seven years, however, would be spent engaging in bitter disputes with various publishers including Grant Richards in London, and Maunsel and Co. in Dublin. After a series of fitful agreements with both publishers, including a dispute that resulted in George Roberts of Maunsel and Co. burning copies of Joyce’s manuscript, Dubliners was eventually published in 1914 with Grant Richards. Dubliners is a collection of fifteen short stories, categorised by Joyce into four sections: childhood, adolescence, maturity, and public life. The stories, often depicting moments of personal defeat, were written to showcase Dublin and its people as the centre of paralysis, politically, emotionally, socially, and culturally. The most famous short story, “The Dead”, was hailed as one of the greatest short stories ever written by American poet T. S. Eliot.

Writing to his brother Stanislaus in 1905, Joyce remarked: “when you remember that Dublin has been a capital for thousands of years, that it is the ‘second’ city of the British Empire, that it is nearly three times as big as Venice it seems strange that no artist has given it to the world”. After the publication of Dubliners, Joyce continued to give Dublin to the world in literature.

Joyce’s novel A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, a revised version of his earlier project Stephen Hero, began serialisation, at the behest of American modernist Ezra Pound, in the Egoist periodical in 1914 and 1915. It was later picked up and published in its entirety as a novel by American publisher B.W. Huebsch, resulting in Joyce naming 1916 his annus mirabilis.

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man is a semi-autobiographical novel that follows the protagonist of Stephen Dedalus, using the same pseudonym as he used in The Irish Homestead. While Stephen Dedalus follows many of the same paths as Joyce himself, including attending Clongowes, Belvedere, and UCD, Joyce retained an ironic distance between himself and a protagonist experiencing and questioning issues of nationality, religion, creativity, and language. Joyce’s novel acts as both a Bildungsroman, a coming-of-age story, and an Kunstlerroman, a novel about the growth of an artist.

By 1918, Joyce had also completed work on his only play, a European-theatre-influenced work entitled Exiles. Centred around Irish writer Richard Rowan and his wife Bertha, and a series of former passions and jealousies. The play was, however, rejected by W.B. Yeats for production at the Abbey Theatre and received generally poor reviews including a bitterly negative review of its August 1919 production at the Munich Schauspielhaus. The play was performed in 1970 by Harold Pinter and received more favourable reviews than its early iterations.

In Autumn 1907, Joyce hatched the first ideas for what would become Ulysses, a novel that would cement his place in the annals of literary history, contribute to the nascent modernist project, and ultimately change modern literature.

Joyce worked on Ulysses regularly, having started the first pages of the third chapter by June 1915. The novel was serialised in The Little Review from 1918 until 1920 when an excerpt that was deemed obscene prompted its unceremonious removal from the periodical. Issues of the magazine were seized by the Post Office and prevented from being distributed.

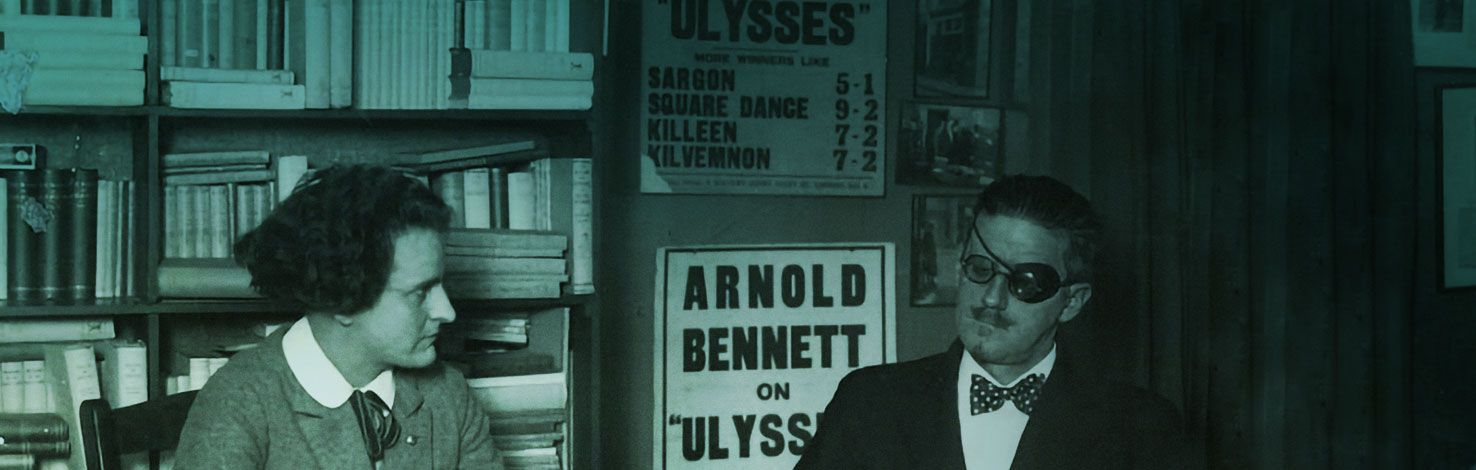

Joyce continued working on Ulysses when Sylvia Beach, owner of the Shakespeare and Co. bookshop in Paris offered to publish the novel in its entirety. The novel was published on Joyce’s 40th birthday in 1922 and stirred many controversies as a result.

Ulysses follows the character of Leopold Bloom, a half-Jewish ad canvasser, in Dublin on 16 June 1904. The date of the novel’s setting is a reference to the first date Joyce and his future wife Nora Barnacle shared in Dublin. The novel also follows Stephen Dedalus, continuing his narrative in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, and the final chapter depicts the inner thoughts of Molly Bloom, Leopold’s wife, as she lies in bed.Using parallels to Homer’s Odyssey, Joyce’s novel illustrates the everyday life in a colonial capital city, including its politics, culture, history, and perhaps most importantly, the trappings of everyday life. Despite its simple plot, the novel is wholly experimental. Throughout Ulysses, Joyce uses stream of consciousness, free indirect speech, and unreliable narrators. In some chapters, Joyce parodies romance fiction, while in others he satirises the language of Irish nationalist mythology. In the “Oxen of the Sun” episode set in a maternity hospital, Joyce’s prose parallels the development and maturity of English literature. The novel also included historical, and political discussions, music, and foreign languages. Joyce said of his novel: “I’ve put in so many enigmas and puzzles that it will keep the professors busy for centuries arguing over what I meant, and that is the only way of insuring one’s immortality”.

As a result of its frank discussions of sexuality, and depictions of the realities of everyday life, the novel was deemed obscene. Ulysses was consequently banned in the United States after an obscenity trial that resulted in a conviction which was not overturned until 1933.

After the exhausting and exhaustive achievement of Ulysses, coupled with failing eyesight, Joyce took a year to rest before hatching new ideas for further work. In March 1923, Joyce wrote to his patron Harriet Shaw Weaver: “Yesterday I wrote two pages—the first I have since the final Yes of Ulysses. Having found a pen, with some difficulty I copied them out in a large handwriting on a double sheet of foolscap so that I could read them”. These pages went on to become Work in Progress, the backbone to what would become his final work, Finnegans Wake.

This new work began to alienate even some of Joyce’s most ardent supporters, including Harriet Shaw Weaver, Ezra Pound, Wyndham Lewis, and his brother Stanislaus. It was, however, serialised in the transition magazine from April-November 1929 by Eugene Jolas. A defence of the work was also published by Samuel Beckett, William Carlos Williams, Frank Budgen, and others.

In the midst of his intense work on Work in Progress, Joyce published a second collection of poetry, Pomes Penyeach, in 1927. It received a weak critical reception.

Joyce feverishly attempted to finish Finnegans Wake, and eventually published it on 4 May 1939, 16 years after beginning. The novel deals with Humphrey Chimpden Earwicker, also known as HCE or “Here Comes Everybody”, who has been accused of a crime in the Phoenix Park. In many ways, Joyce expounded the complexity and experimentalism of Ulysses in his new novel. The novel contains dream sequences, puns, stream of consciousness, literary allusions, and more. Joyce also began using portmanteau words, including “absinthe-minded”, “laughtears”, and “cropse”. The novel, though difficult, showcases Joyce’s immense creativity in manipulating language and creating new meaning.

Although Joyce died in 1941 — not two years after the published Finnegans Wake — some of his unpublished works have been published. In 1944, Stephen Hero, the precursor to A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, was published and subsequently banned by the Irish Censorship Board.

Joyce’s The Cat and the Devil and The Cats of Copenhagen, both short stories written for his grandson Stephen in 1936, were published in 1957 and 2012, respectively.