Work

Ulysses (1922)

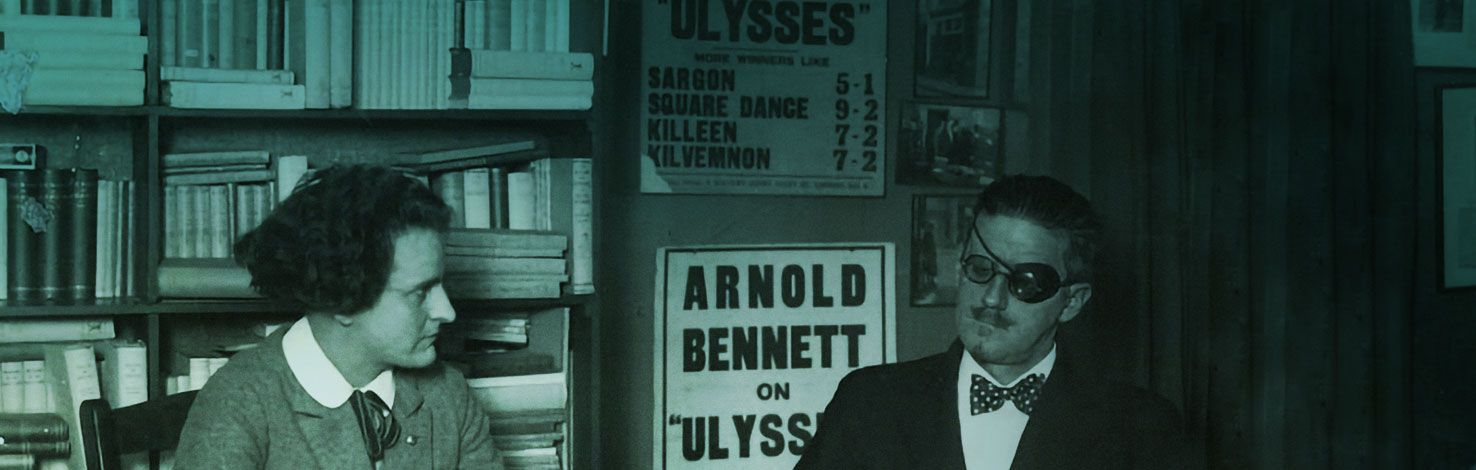

On 2 February 2022, Ulysses celebrated the centenary of its publication. Ulysses is James Joyce’s most celebrated work and is lauded as being both a paragon of modernist literature and notoriously hard to understand. Joyce himself went so far as to poke fun at this fact in his even less-intelligible Finnegans Wake: “amid the insipissated grime of his glaucous den making believe to read his usylessly unreadable Blue Book of Eccles”. The “Blue Book of Eccles” is, of course, a reference to the Aegean Sea blue colour of the very first edition published by Sylvia Beach’s Shakespeare and Company Press in Paris on 2 February 1922, Joyce’s fortieth birthday.

Initial preparation for Ulysses began in 1902 when Joyce was just twenty years old. He was self-possessed enough to gather all his epiphanies and begin arranging them to form notes. He began work in earnest in 1914 after the publication of Dubliners and continued writing it for another eight years.

Among its many features, Ulysses deals with the opulence of personal thought. While we are ushered into the private world of its characters with ease, we know relatively less about their exteriors. Moreover, the novel is a modern adaptation of Homer’s Odyssey, with several of its characters and events brilliantly but unevenly based on the Homeric epic.

The novel follows the main character Leopold Bloom, a non-practising Jew, in Dublin on 16 June 1904. Throughout the novel, the reader is permitted to become wholly familiar with the inner workings of Leopold’s mind but not given nearly as much information about his physical appearance to form a clear mental picture of him. We are told he is quiet and decent, a man of inflexible honour to his fingertips. He has a pale intellectual face in which are set two dark large lidded, superbly expressive eyes. The story of a haunting sorrow is written on his face and his friends say that there’s a “touch of the artist” about old Bloom. A safe, moustached man who has his good points and slips off when the fun gets too hot. He is both a modern-day Odysseus and an Everyman, trying his best to navigate the dirty streets of Dublin and a wider world that can feel foreign and overwhelming.

Stephen Dedalus, whom we first meet in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (and, according to some scholars, in Dubliners), is another figure winding his way through the streets of Dublin in the novel. Stephen is an arrogant young intellectual whom Bloom takes under his wing. Cerebral, tortured, and brilliant, Stephen is Joyce’s alter ego. He strives to become an artist in the stifling, poor environment that was 1904 Dublin, rebelling against his church, his nation, and nearly everyone around him in the process.

Sometime during the day, Stephen and Bloom cross paths. Bloom acts as a father figure to the young Stephen, whose own father Simon is distant and tragic. For his part, Stephen fulfils the role of a son for Bloom, whose own son died in infancy. Their relationship is the focus of the latter-third of the novel, Stephen’s Telemachus traveling alongside Bloom’s Odysseus.

Molly Bloom, Bloom’s wife, is equated with Penelope in The Odyssey and the last chapter of the book is dedicated solely to her meanderings and musings. It is one of the most renowned pieces of writing in Ulysses and is famous for its celebration of this voluptuous, sensuous, opulent, abundant, independent, lush, and blooming woman.

Ulysses has for one-hundred years shocked, inspired, provoked, and puzzled readers around the world. Considered on the best novels of the twentieth century — if not of all time — Ulysses continues to work its magic. “I’ve put in so many enigmas and puzzles”, Joyce wrote of his book, “that it will keep the professors busy for centuries arguing over what I meant, and that is the only way of insuring one’s immortality”.

Dubliners (1914)

Dubliners is a collection of vignettes of Dublin life at the end of the nineteenth century written, by Joyce’s own admission, in a manner that captures some of the unhappiest moments of life. The work contains fifteen short stories with some of the dominant themes including lost innocence, missed opportunities, and an inability to escape one’s circumstances.

Joyce’s intention in writing Dubliners, in his own words, was to write a chapter of the moral history of his country, and he chose Dublin for the scene because that city seemed to him to be the ‘centre of paralysis’. He tried to present the stories under four different aspects: childhood, adolescence, maturity, and public life.

“The Sisters”, “An Encounter”, and “Araby” are stories from childhood. “Eveline”, “After the Race”, “Two Gallants”, and “The Boarding House” are stories from adolescence. “A Little Cloud”, “Counterparts”, “Clay”, and “A Painful Case” are all stories concerned with mature life. Stories from public life are “Ivy Day in the Committee Room”, “A Mother”, and “Grace”. “The Dead” is the last story in the collection and probably Joyce’s greatest. As the title suggests, it is concerned with mortality, the culmination of life’s varied and bitter experiences. It stands alone as one of the greatest short stories ever written in the English language.

After seven years engaging in bitter disputes with various publishers, Dubliners was eventually published in 1914, not in Dublin as Joyce had originally hoped but in London by Grant Richards.

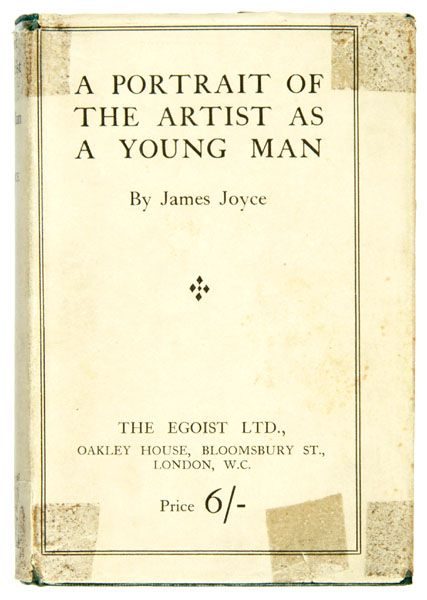

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916)

In this semi-autobiographical novel A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Joyce sets forth the childhood, adolescence, and early adulthood of Stephen Dedalus, his alter ego. He travels through Stephen’s mind and soul allowing us to experience his mental and spiritual development whilst witnessing the physical changes he goes through as he matures. Joyce, as part of the early twentieth century modernist movement, was involved in reinterpreting the form of the traditional novel as plot-driven narrative. By rejecting traditional narrative form in A Portrait, Joyce moved towards internalising the action within Stephen’s mind, a movement from narrative driven plot to internalised rhythmic moods.

In A Portrait, what happens inside Stephen’s head is actually more important than what happens in the physical world. The other characters in the novel exist to further display Stephen’s character and its development in relation to their own singular lack of artistic awareness.

As Stephen gets older and more introspective, the other characters become less well-defined. We get detailed snippets on his mother, father, and siblings that are more telling in their brevity than in their candour. This novel is a work of highly polished precision writing, lyrical and poetic in its observations of both poverty and intellectual reverie.

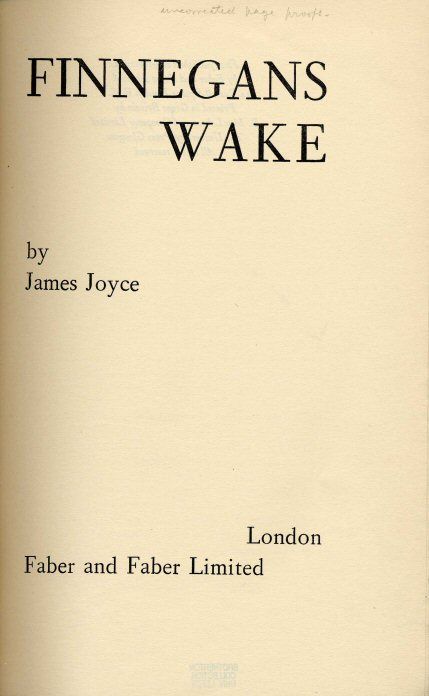

Finnegans Wake (1939)

Finnegans Wake, Joyce’s final work, was written over a period of sixteen years with composition starting in 1923. It was finally completed and published in May 1939. Like all of Joyce’s work, Finnegans Wake was dogged by publication controversy. The obscurity of the text meant that many lost faith in his last artistic venture, finding it too cryptic to relate to. In the end it was his own innate belief in his artistic mission and the support of a number of close allies that carried him through to complete the work.

The title came from the popular Irish ballad about a hod carrier (brick transporter in the construction industry of the time) called Finnegan, who falls to a supposed death from a building but is revived by a shot of whisky thrown in the drunken mêlée that ensues at his wake. Joyce kept the title of the work a closely guarded secret for many years whilst issuing sections of the work for publication entitled “Work in Progress”.

The period of composition was the most trying of his Joyce’s life. His health was unstable due to recurrent eye problems and stomach ulcers. He was often enveloped in a darkness of sight, akin to the darkness of the unconscious he was so concerned in trying to articulate. During this period his son Giorgio’s marriage floundered and his daughter Lucia’s mental health deteriorated devastating Joyce.

Whilst his private life was troubled, in his public life Joyce had become synonymous with the modernist artistic movement and, although he lived a life quite removed from Parisian bohemianism, he was famous as the author of Ulysses. As an artist, he had arrived.

Finnegans Wake is a novel written using the dream form as a device to tell the universal story of Everyman, Humphrey Chimpden Earwicker, his wife Anna Livia Plurabelle, and their children, twin sons Shem and Shaun and daughter Isabel. The novel also recounts the history of Ireland, the history of the world and tells the tale of a river rising in Poulaphouca, Co. Wicklow and flowing through the heart of the city of Dublin into Dublin Bay. The dream form allowed Joyce the space and freedom to introduce unfettered, myriad strands of material into the language of the night and the unconscious.

The novel is divided into four main parts called “books”. These in turn are subdivided into seventeen “chapters”. The language of the novel employs multilingual puns, songs, jokes, polyglot portmanteau words, allusions, scientific information, myths, and legends.

The content of the novel is vast. Much of the text is based on or inspired by the eclectic material Joyce collected in his copious notebooks, including fragments of information, phrases, and passages drawn from books, magazines, journals, and ephemera. Finnegans Wake has earned itself an undeserved reputation for being incomprehensible and unreadable.

This could not be further from the truth. It is, enigmatic as it may be, work of awesome beauty into whose inky depths one can probe for years. Its content is rich and varied and also sonorously lyrical. With the correct tools and frame of mind, the amazing journey of discovery and revelation that is Finnegans Wake can easily begin.

In the words of Joycean scholar Danis Rose, “Finnegans Wake is a big dream: one for the tribe”.

Other Works

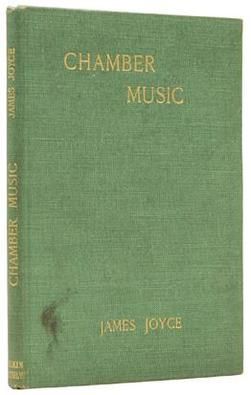

Chamber Music (1907) and Pomes Penyeach (1927)

Although not renowned for his poetry, Joyce’s work in this area is accomplished. Chamber Music is a collection of thirty-six of Joyce’s poems. Chamber Music is essentially a collection of love poems written in different styles, composed and revised between 1901 and 1906. Elkin Mathews of London published the first edition in 1907, the same year he refused Joyce’s manuscript for Dubliners.

In 1927 another book of his poetry, Pomes Penyeach, was published by Shakespeare and Company. This short collection of thirteen poems is the only other title of Joyce’s that Sylvia Beach published.

Joyce wrote many other poems such as “Gas From a Burner” and “The Holy Office”, both polemical attacks on Irish society. Among his other renowned poetical works is “Ecce Puer”, a poem dealing with the death of his father John Stanislaus Joyce and the birth of his grandson, Stephen Joyce.

Exiles (1918)

Joyce also turned his hand to theatre and, inspired by the work of Henrik Ibsen, produced Exiles in 1918. Exiles contains many of the themes that repeatedly feature in Joyce’s work but, unlike A Portrait and Ulysses (between which Exiles was produced), it never managed to attain the same status of success as Joyce’s novels.

The play is set in 1912 Dublin and the plot revolves around the character of Richard Rowan and his intellectual dilemmas as to whether he should settle down in Ireland as a lecturer in Romance Languages or flee the nest as Joyce himself did. There is a fear that if he decides to stay it will leave him in a state of paralysis and bitterness. At the play’s end we do not find a resolution, only a deep longing for love and understanding on the part of Bertha, Richard’s wife, and a deep weariness on the part of Richard himself.

The play has much autobiographical content relating to Joyce’s early experiences of exile in continental Europe. One also gets an insight into Joyce’s preoccupation with jealousy and betrayal in love. Exiles was rejected by numerous establishments in England, Ireland, and the United States, including W.B. Yeats at The Abbey Theatre. Published in London by Grant Richards, his old publisher of Dubliners, in 1918, it was first produced in Munich in 1919. Since then the only significant production arguably came from Harold Pinter in the Mermaid Theatre, London in 1970.